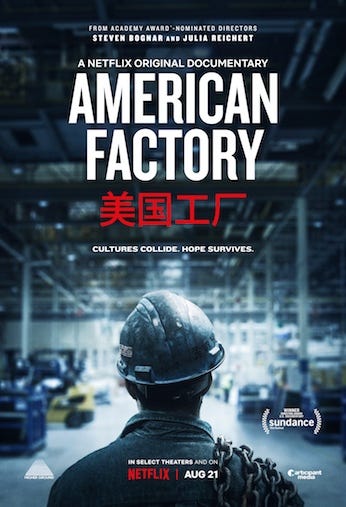

'American Factory' review: Stunning

Documentary shows globalization's effects on Dayton plant and its workers

What makes the new Netflix documentary “American Factory” so masterful is the way filmmakers Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert let everyone speak for themselves.

There’s no narrator in the film, which chronicles the reopening of the former GM assembly plant outside Dayton, Ohio, by Chinese glass manufacturer Fuyao. That means we get to see the culture clashes and the stunning ways globalization has altered the expectations of American life played out in the words of those involved.

And that is no small feat. The concept of globalization is a complicated one, often driven by macroeconomic forces and massive governmental policies. To see how it plays out every day in the lives of people eager to earn enough to move into their own apartments or struggling to balance safety and pressure for profits is remarkable.

Bognar and Reichert landed incredible access from Fuyao, who initially wanted to hire them to tell a feel-good story of the return of thousands of manufacturing jobs to Dayton. The filmmakers declined so they could maintain editorial control, but Fuyao still let them document meetings and interviews that were shocking in their anti-American and anti-union biases.

“You all know how we stand on this,” Fuyao founder and CEO Chairman Cao Dewang says. “We don’t want to see the union developing here. If we have a union it will impact our efficiency, thus hurting our company, it will create loss for us. If a union comes in, I’m shutting down.”

When Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) mentions a UAW organization drive at the plant during his speech at Fuyao’s grand opening, one of the plant’s managers jokes about wanting to chop off his head.

There are comments from Chinese managers about how the American workers are slow and have fat fingers, how they talk too much and dress sloppily. Seeing stereotypes so blatantly discussed – in training sessions, no less – is unnerving, as are the scenes where Chinese managers boast about how they have fired union sympathizers, even though many of them were simply just concerned about workplace safety. These are complaints that manufacturing workers have long lived through, but could rarely prove because of a lack of documentation.

However, “American Factory” isn’t really out to show a single point of view. Though Fuyao is against a union for its American factory, it has them in China. It shows how Fuyao’s Chinese workers are more willing to do whatever it takes to ensure the company’s profitability than their American counterparts, though the Chinese workers are certainly not happy working 12-hour days or six days a week. And Fuyao is certainly taking a risk opening a manufacturing plant in Ohio, when globalization has created so many cheaper labor sources around the world. (Of course, tax incentives and the proximity to customers figure into the calculation. It’s not simply some sort of altruistic gift to the community.)

Both the Chinese and American workers talk about their worries to make ends meet and doing what is necessary to take care of their families. It becomes pretty clear they have more in common with each other than their owner who pits them against each other.

Maybe the most chilling scene comes at the end, when Chinese managers show off automation at the Dayton plant and proudly talk about how many workers have been laid off because of it. All these growing pains that come with globalization may become obsolete, as robots take away more and more manufacturing jobs. Automation is the complicated development on the horizon.

Globalization is the complicated development workers are dealing with now. And “American Factory,” the first film to be distributed by Barack and Michelle Obama’s new Higher Ground production company, offers a poignant, straightforward look into what they face. Maybe seeing these issues so plainly will help convince global leaders about the importance of solving them. — GLENN GAMBOA